When you look at the joke that John Travolta is today — his vast, meaty face occupying half the screen in “Wild Hogs,” or his just-barely-fatter dress-wearing self frolicking with Christopher Walken in “Hairspray” — it’s hard to believe that he used to be hugely popular. In fact, he’s been hugely popular TWICE, first in the late ’70s and again in the mid-’90s, when Quentin Tarantino launched his comeback, a deed that now seems like an act of terrorism.

It was during this country’s shameful Disco Era that Travolta first became a phenomenon. His dancing skills and vaguely ethnic good lucks captured the hearts of all the people in America who had easily captured hearts. He also dazzled us with his wide range of acting skills, playing everything from an imbecile Brooklynite in “Welcome Back, Kotter” to an imbecile Brooklynite in “Saturday Night Fever.” There were also occasions when he played imbeciles who were from other places but who had Brooklyn accents. The world was John Travolta’s oyster. Or oysta, rather.

Then came “Staying Alive.” It was nominally a sequel to his 1977 smash hit “Saturday Night Fever,” which had been about a preening disco stud named Tony who treated women like garbage. (Actually, his attitudes toward women were a little more complicated than that. To transform himself from daytime paint-store employee to nighttime disco god, Tony would primp his hair, adorn himself in jewelry, pour his slender, lithe body into a highly fashionable white suit, and then go dancing. In other words, to be somebody special, Tony had to become a woman. It is no wonder, then, that he was so confused, treating women like nuisances and whores one minute, saviors and goddesses the next. This concludes the Gender Studies portion of this week’s film lecture.)

“Staying Alive” was released in 1983, a full six years after “Saturday Night Fever” and a good three years after disco fever had disappeared, leaving all of America’s youth feeling clammy and humiliated, the way you feel when you wake up after a night of partying to discover you’ve slept with a lazy-eyed karaoke waitress with a wooden leg. The sequel moves Tony from Brooklyn to Manhattan and changes his style — he doesn’t do a single step of disco dancing — but thankfully retains the misogyny and general douchebaggery that made him so popular in ’77.

We find him living in a fleabag hotel near Times Square, teaching dance classes by day and serving drinks in a dance club by night. In between, he auditions, going from one casting agent to the next to deliver copies of his headshot (which you’d think, considering it’s Travolta, would have to be poster-size). Tony’s girlfriend, Jackie (Cynthia Rhodes), a feathery-haired wallflower, is a dancer too, and is currently in the ensemble of a Broadway show that eschews plot and dialogue in favor of vigorous, unsexy dancing. On the show’s closing night, Tony comes to watch from backstage — but, being a complete a-hole, he ignores Jackie’s performance and remains fixated on the lead, Laura (Finola Hughes), a long-haired British import who evidently earned her starring position by being the most vigorous and least sexy dancer at the audition. Watching her dance is like watching Laraine Newman have a seizure.

After the show, while sweet Jackie is changing out of her costume, Tony brazenly flirts with the cold, manipulative Laura, eventually persuading her to go on a date with him. When Jackie returns, unaware of what Tony’s been up to, he has the gall to ask her whether Laura is dating anyone. Later, Tony and Laura go out, then have sex in her apartment while Bee Gees songs play on the soundtrack. (The film’s opening credits declare, “Featuring songs by the Bee Gees,” as if that’s something to be proud of.) After their romp, Laura kicks him out. It’s 3 a.m. From a pay phone, Tony calls Jackie and euphorically chats with her for a minute. He doesn’t try to come over and sleep with her. He doesn’t tell her where he’s been. He just … calls her. She seems to think it’s cute that he woke her up for no reason, the same way she thinks every other stupid thing he does is cute.

We learn that Jackie occasionally sings with a barroom band fronted by Frank Stallone. (The only possible explanation for Frank Stallone and his music appearing in a film is that his brother Sylvester is the film’s director; sure enough, that is the case here. Notice I say it’s an explanation, not an excuse.) In a bit of astonishing hypocrisy, Tony is enraged to see Jackie behaving in a friendly manner with Frank Stallone, furious that she would even LOOK at another guy. Jackie soothes Tony’s ego, however, and gives assurances that she loves only him. Tony is placated, promises he’ll be back when the bar closes to pick her up, and then totally blows her off so he can lurk outside Laura’s apartment instead.

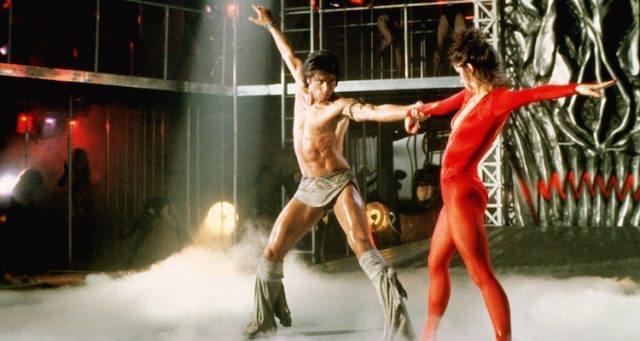

Meanwhile, Tony and the two spineless women in his life have all gotten parts in a new Broadway show. It’s called “Satan’s Alley,” and speaking of Satan’s alley, this show seems to be right up it. There is no talking or singing, only dancing, set to prerecorded cheese-rock songs and enacted by dancers in skintight leotards and leg-warmers. Imagine “Cats,” only without the complex story line, and with more suicides among audience members.

Laura, who is independently wealthy and wears a fur coat everywhere, has the lead in the show, but her dance partner is having trouble conveying the director’s unique vision, which seems to consist of a lot of writhing. Tony thinks this might be his big chance, so he asks Jackie to help him practice so that he can replace Laura’s partner in the show. For some reason, Jackie agrees to this.

(Actually, I shouldn’t suggest Jackie’s reasons are mysterious. It’s actually obvious why Jackie helps Tony get closer to Laura: because Jackie is a moron.)

Tony continues to flit back and forth between his two women, each of whom has a different way of dealing with him. Jackie’s method is to go along with whatever he says and instantly forgive him after he’s been a jerk, provided he offers a halfhearted apology and a cute smile. Laura, on the other hand, prefers to be cold one minute and flirtatious the next, often literally turning from one to the other within the span of a 30-second conversation, irrespective of anything Tony has said.

At one point, Tony starts to feel remorse for being a gigantic bastard, so he goes home to Brooklyn to gather his thoughts. (Brooklyn is where you get your best soul-searching done.) He tells his mother (Julie Bovasso) that he’s sorry for his prickly behavior, but she stops him. She says it’s OK because that’s who he is — i.e., an arrogant creep — and that his bastardry must be a good thing because it helped him get out of this dead-end neighborhood and onto Broadway. This is the movie’s way of avoiding any actual character development for Tony. You keep thinking he’s going to learn to be a better person and treat Jackie right, but now we have it on no less an authority than Tony’s own mother that his behavior is, in fact, wholly acceptable. If you don’t like it, well, that must be YOUR problem.

Inevitably, we come to opening night for “Satan’s Alley.” The director, a bearded man whose name is never mentioned, is up in the booth calling the lighting cues himself. (I guess he’s such a control freak that he doesn’t trust the stage managers to do their job. That, or no one involved in this film knew how live theater actually works.) The show opens with a large-scale dance number, involving the entire cast, in which everyone except Tony and Laura writhes around on the floor while Tony and Laura writhe around each other. After this opening number, the stage is bare and silent for two or three minutes while the cast changes costumes. Then they do another number that’s suspiciously similar to the first one, and then more dead time as they all change costumes again. This has got to be the worst Broadway show ever produced, and I say that having seen “Young Frankenstein.”

“Staying Alive” ends with Tony so thrilled by his Broadway success that all he wants to do is strut around Manhattan in tight jeans while the title song blares on the soundtrack. As he does this, we get several close-up shots of his butt, and at least one of his package. This may seem like shameless pandering to the film’s target audience of horny teenage girls, but at least it gives us a few moments’ respite from Travolta’s wide, misshapen face.