The life of Panamanian boxer Roberto Duran has featured enough drama, setbacks, and victories to make for a terrific movie. Maybe someday someone will make one. In the meantime, here’s “Hands of Stone,” another well-intentioned but feckless snooze.

If it seems like about 75 percent of sports biopics could be described in equally weary terms, well, yeah. Tell me about it. Believe me, critics are as tired of being disappointed by generic biographies as you are of hearing about them.

Based on Christian Giudice’s biography of Duran, adapted and directed by Venezuelan filmmaker Jonathan Jakubowicz, “Hands of Stone” begins in the usual fashion: a scene somewhere in the middle of the person’s career to establish what he would become — in this case the Benny Huertas fight at Madison Square Garden in 1971 — before jumping back in time to see how he got there. In 1964, Roberto is a 13-year-old scamp in the slums of Panama, learning boxing from portly Plomo Quiñones (Pedro Perez) and street smarts from Chaflan (Oscar Jaenada), a clownish Pied Piper figure. Later, these two mentors will be among the people that the successful, prideful Roberto turns his back on.

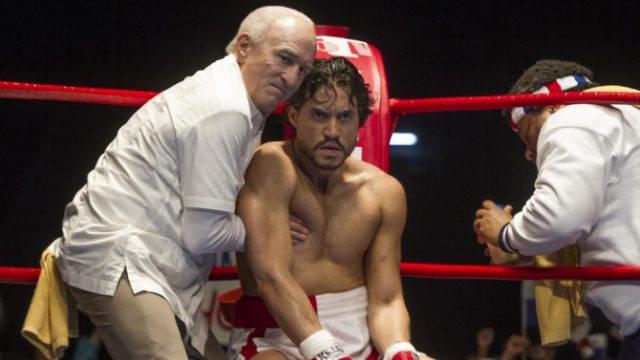

In the ’70s, Duran (played by Edgar Ramirez) comes to be trained by Ray Arcel (Robert De Niro), one of the great old-school boxing coaches. Ray, an elderly Jew whose insults are sprinkled with Yiddish words, also narrates the film, and includes a flashback to 1953, when he’s forced out of the professional boxing world by the Mafia (represented by John Turturro), who gives him a simple choice: if he ever makes money as a trainer again, the Mob will kill him. He therefore coaches Duran for free.

That backstory with the Mafia is an interesting detail, but it muddies the water. Whose biography is this, Duran’s or Arcel’s? We’re presented with other irrelevant aspects of Arcel’s life, too, including an estranged daughter who appears in two scenes and serves no thematic function. It’s symptomatic of Jakubowicz’s larger problem, one that plagues so many biopics: instead of sorting through the facts to find the clearest, most direct story, he tries to cover everything.

As for Duran, he gets rich and famous in the ’70s (cue the montage of victories mingled with the births of his children), then challenges Sugar Ray Leonard (Usher Raymond) in 1980, hoping to score a symbolic victory for Panama.

You know what happens next. Even if you’ve never heard of Roberto Duran, you know what happens next, because you’ve seen these movies before. He’ll get wealthy and complacent; he’ll gain weight; he’ll be a jerk to his wife (Ana de Armas); he’ll forget the little people; at last he’ll be humbled and stage a comeback. Once we get to a good stopping point, the movie will show us photographs of the real Duran, Arcel, et al., accompanied by title cards telling us what happened next. You know the drill.

Following a template isn’t necessarily wrong. We’ve seen formulaic movies that were riveting and well-told. But “Hands of Stone” is a tedious, mechanical bore that offers no insight into Duran’s character and can’t even seem to figure out what story it’s telling. Not only are there tangents exploring Ray Arcel’s life, there are a few scenes about Sugar Ray Leonard and his wife (Jurnee Smollett-Bell). Even when the film stays focused on Duran, it gets sidetracked, with pointless scenes like the one where he meets his deadbeat father, previously unmentioned and never seen again thereafter.

For what it’s worth, the boxing sequences are competently staged, though nothing special. You’d definitely learn more about Roberto Duran by watching YouTube clips of his fights.

C- (1 hr., 51 min.; )