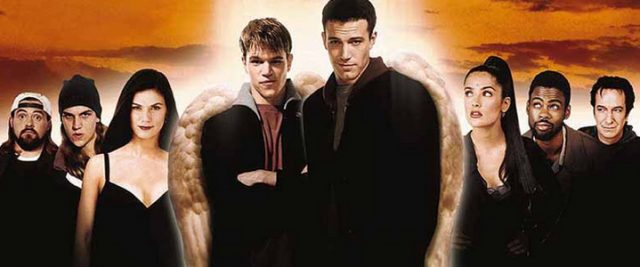

Kevin Smith nearly always adheres to the principle of “write what you know.” That’s why “Dogma,” his controversial 1999 comedy, is brimming with Catholicism, skepticism, profanity, poop jokes, movie references, and Ben Affleck. If you were to cut Kevin Smith’s head open — and I’m not suggesting you should do this — Dogma is probably what would spill out.

Do you remember the ruckus this caused near the end of the last millennium? After a version of the script leaked on to the Internet, the Catholic League, led by William Donohue, vehemently denounced the film as blasphemous. Smith got death threats, which he cheerfully posted on his website. Protesters exerted so much pressure that Disney, which was going to distribute the film through Miramax, got skittish and sold it to Lions Gate, which had not yet adopted its policy of only distributing movies with “Saw” or “Tyler Perry’s” in the title.

Protests continued once the film was actually released, on Nov. 12, 1999, with approximately the same effect that such protests usually have, i.e., drawing more attention to the movie. “Dogma” was Smith’s fourth film, and it easily out-grossed the previous three combined. In terms of tickets sold, it’s still his most successful movie (though this year’s “Cop Out” made more money, as did “Zack and Miri, barely”`).

Yep, nothing sells like controversy. But watching the film, I don’t get the impression that Smith set out to make trouble, or at least not any more than usual. As he observed repeatedly in interviews at the time, the film has a pro-faith message. The main character, Bethany (Linda Fiorentino), was raised Catholic and still goes to Mass every Sunday but has lost faith in God. In the course of the film, her faith is renewed, although I think once you actually see God face-to-face you have to stop calling it “faith” and start calling it “knowledge.”

The film asserts two basic Christian beliefs: that there is a God, and that Jesus Christ is the Savior. In fact, it doesn’t even really assert them — it ASSUMES that they are true, right from the beginning. Of course, it could simply be that the story takes place in a universe where God and Jesus are real, without reflecting on whether Smith actually believes it. But it seems like he does. Regardless of his personal beliefs, the film presents faith in God as a positive, laudable thing.

And it’s also filthy. Just relentlessly filthy. You know how Kevin Smith movies tend to be. I suspect this was at the root of many people’s opposition to it. To discuss matters of doctrine and spirituality in such a vulgar context is jarring, even if the doctrines themselves aren’t being mocked. And unlike” Monty Python’s Life of Brian,” where Jesus himself is treated reverently, both Father and Son are the object of some nasty language in Dogma. Smith is always fond of shock-value jokes; to him, these subjects were no more off-limits than anything else. (Or, to put it another way, it’s the fact that they’re supposed to be off-limits that makes them appealing as joke fodder.)

No doubt some of the more orthodox Catholics were bothered by the actual ideas expressed in the film, too. One character asserts that God is a woman. Another asserts that Jesus was black, and that he had 13 apostles. It’s suggested that the devotion many Christian faiths have to the image of Jesus dying on the cross is morbid and unsettling. (“Christ didn’t come to earth to give us the willies!” says the cardinal.) Since these ideas, and others, go against the standard teachings of the church, you can see why some people would be appalled to hear them bandied about so freely. There’s also the fact that the main character works in an abortion clinic. With that detail, I suspect Smith was trying to push people’s buttons.

Smith draws on a number of myths and traditions here, including some that go beyond Catholicism. Metatron, the messenger angel played by Alan Rickman, appears mostly in ancient Jewish literature, and fills essentially the role that’s described in the movie. Loki (Matt Damon) is from Norse mythology (except he was a god of mischief, not an angel of death), and Azrael (Jason Lee) is found in Islamic and non-canonical Christian writings (except he’s the angel of death, not a mid-level demon).

Smith falls prey to a misconception about Catholic belief, though, and it’s kind of major. In the film, Loki and Bartleby (Ben Affleck) are fallen angels who have been banished from heaven. They find a loophole: the cardinal is re-dedicating a particular church in New Jersey, and on that day anyone who passes through its arch will receive “plenary indulgence,” or a forgiveness of their sins. If Loki and Bartleby pass through the arch, they’ll be spotless, and then God will have to let them into heaven, assuming they hurry up and die before they break any commandments.

The problem is, while it’s a common misunderstanding, that’s not what plenary indulgence actually is. The actual teaching is that receiving an indulgence merely lets you skip the temporal punishment for your sins (where you have to pray, fast, perform works of mercy, and so forth). To be forgiven, you still have to go to confession and take communion. What’s more, you have to do those things BEFORE you can get a plenary indulgence. You’d think Loki and Bartleby would know this. Then again, you’d think the other characters in the movie would know it, too. Like I said, the movie came out of Kevin Smith’s head. It can only reflect what’s in there, rattling around next to images of hockey sticks and Stormtroopers.

— Cinematical