I recently marked the 20th anniversary of the first time I kissed another male gentleman of the same gender as myself (boy). We were students at Brigham Young University, and we met exactly where you’d think: in a support group for BYU students who were trying not to be gay. The fact that our relationship never got more intimate than kissing is probably that support group’s greatest success story.

I was 23, and it had only been six months since I first told anyone I was gay. (I don’t count the time, three years before that, when I was a missionary and my mission president asked if I was gay and I said yes, because I never would have told him if he hadn’t asked.) The first person I told willingly, back in October 1997, was my friend Rob, whom I’d known only since the start of the semester. I told him because I suspected (correctly) that he was in the same boat, gaywise. We sat in Pedro, my 1987 Hyundai Excel, and had a tearful heart-to-heart while parked on the hill near the Provo Temple, surrounded by other parked couples who were making out and/or getting engaged.

Rob and I were typical BYU students: Mormons, returned missionaries, total dorks, ostensibly looking for wives (one apiece), and committed to premarital celibacy by our religious beliefs and by the university Honor Code. Being what bitter ex-Mormons sarcastically call a TBM — True Believing Mormon — I was trying to figure out how I fit into things on account of the gay.

“Same-sex attraction,” to use the vernacular of the day, wasn’t itself against Mormonism or the Honor Code; after all, one doesn’t choose whom one is attracted to. But Mormon culture at the time didn’t do a great job of making the distinction between thoughts and behavior. A 1997 survey showed 91% of BYU students claiming to understand the LDS Church’s position on same-sex attraction, but when asked for details, only 33% actually got it right. If people at BYU knew you were gay, they tended to assume you were in violation of one rule or another and view you with self-righteous suspicion, self-righteous suspicion being one of BYU’s chief exports. (That same survey showed 42% of students believing gay students shouldn’t be allowed at BYU even if they didn’t do anything wrong.) So most of us kept quiet about it.

In that spirit, Rob and I pledged to keep each other’s secrets and support one another as friends in our efforts to minimize our homosexuality. That was the verb we used: “minimize.” We accepted that the gay probably wasn’t going to vanish entirely regardless of faith, works, or wish-granting genies. But we believed we could minimize the gay, the way you minimize a window on a computer. The application is still running — there’s no way to force-quit it, no matter what you may have heard — but it’s just a little icon down in the corner, out of the way, invisible unless you bump into it (in which case it is READY FOR ACTION!). You can go about your normal, heterosexual life and hardly even know it’s there.

Theoretically, that is. We didn’t know anyone who had actually done it, but it sounded plausible.

Anyway, Rob isn’t the one I kissed. The gayest thing we did together was go to the gym. A few weeks before we came out to each other, I started seeing a therapist (whom I also did not kiss) through BYU counseling services. His name was Ken — Ken the Kounselor, as I called him in my journal. My journal says that my objective in talking to Ken was to help me cope with depression, but my journal is being coy. While I was indeed struggling with that, my objective with Ken was to un-queerify me, which I assumed would fix the depression.

My journal during this period omits, avoids, or writes around all references to my being gay. I was so closeted I wasn’t even out to my own journal. My thinking at the time was that it wouldn’t be long before I’d “minimized” the gay demon, if not slain it altogether, so there was no point in mentioning it. No one ever needed to know. ‘Twould sully the future reader’s image of me, ‘twould.

(I should stress that the de-gayification process we were talking about here only involved that — talking. Whatever arcane “conversion therapy” they used to do was before my time. How old do you think I am? How dare you.)

Ken suggested I attend the weekly support group for same-sex-attracted BYU students, where I would meet other college guys who were just as eager as I was to not be gay. To summarize, the counseling department thought that a good way to help young men lessen their sexual attraction to other young men was to put them all in a room together and have them talk about it. Presumably they would share tips for being less gay — “Don’t go out of your way to spend time with groups of gay people,” for example.

This was manifestly a terrible idea that would likely have the opposite of its intended effect, but that’s only part of the reason I was reluctant to go. The other reason was that around the same time that I came out to Rob and started seeing Ken the Kounselor, I also became BYU-famous.

• • •

As a journalism major, I worked for BYU’s campus newspaper, The Daily Universe, and I’d recently started writing a weekly column called Snide Remarks (GET IT??). Mostly I made jokes about BYU and Mormon culture, jokes the likes of which had not often been made before in the official student publication. Sometimes I made fun of The Daily Universe itself. Due to the combination of BYU students being starved for entertainment and The Daily Universe being distributed free all over campus, Snide Remarks quickly became massively popular. I got emails all the time. People stopped me on campus to talk about it. Even the university president weighed in! (Not a fan.) Strangers said something complimentary about my column to my face multiple times per day, especially on Mondays, when it was published, when everywhere I went I’d see the paper folded open to the page with my face on it.

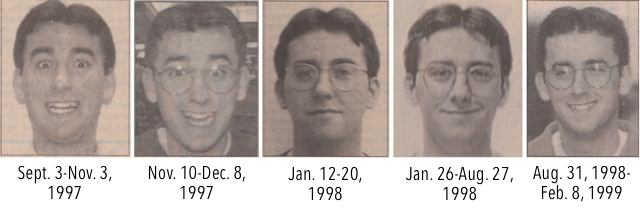

That’s how they knew who I was, you see. The picture. Depending on the day, it was one of these pictures:

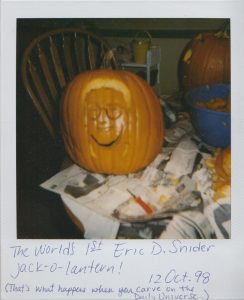

As Mormons, the students at Brigham Young University are very friendly, and they are not shy about approaching strangers. “Hey, you’re Eric D. Snider!” they’d say (or if they didn’t want to seem too eager, “Hey, you’re that Snide Remarks guy!”). I was asked out on dates. I was invited to lunch. Friends and roommates would bemusedly report on acquaintances of theirs who’d been giddy to discover that they knew Eric D. Snider. When we published a compilation of Snide Remarks columns, charging people for content they’d already read for free, the BYU Bookstore sold 1,500 copies in five months (representing some 5 percent of the student body), including 100 on each of the two days I did signings. Somebody carved my face into a pumpkin at Halloween. When I was in the Garrens Comedy Troupe 5th anniversary show in January 1998, three girls attended one performance wearing matching T-shirts with my picture on them, which was deeply disconcerting and remains the closest my face has ever been to a woman’s chest.

I’m not bragging. I mean, I am bragging, but I’m not exaggerating. It was a very surreal way to experience college. As a campus celebrity I had many of the pressures that real famous people have (everyone is watching you) but none of the wealth (everyone is watching you write a check for $1.00 for gum at the bookstore). There are times when you don’t want people to know who you are. I was often worried that something like this would happen:

(As I leave a public restroom.)

BYSTANDER: Hey, wasn’t that Eric D. Snider?

OTHER BYSTANDER: I think so.

BYSTANDER: Well, he sure stunk up the bathroom.

Once I was in the locker room after a P.E. class, freshly showered and clad only in the washcloth-sized prank towel they give you. Just as I dropped the towel so I could start getting dressed — at the moment of maximum nudity — someone said, “Hey, you’re that Snide Remarks guy!” This was an awkward time to be identified, and the best response I could muster was, “I’m surprised you recognized me from that angle,” which doesn’t even make sense.

The point is, if I went to the support group, the other hapless homosexuals there would have the benefit of anonymity, and I would not. I would have the benefit of being asked by strangers, “Hey, are you going to write a column about this?”

But my curiosity and innate tendency toward self-destruction got the better of me, and I went to a meeting. It must have been around February 1998; my journal, unsurprisingly, doesn’t mention it, not even in a watered-down way (e.g., “Tonight I met a group of strangers who also don’t like sports”). There were about a dozen guys present, and I saw several expressions of recognition when I walked in. One was from someone I knew from my apartment complex, an effeminate Southerner who epitomized the notoriously difficult game of Gay or Effeminately Southern? (The tricky devil was both!) “Oh, hi, Eric,” he said, as crestfallen to see someone he knew as I was to see someone I knew. “Welcome to the club.”

I don’t remember what we discussed in the meeting, and I think I only ever went to one other, when they were having a “formerly” gay man and his wife as guest speakers, to show us it could be done. (This was 20 years ago, so I imagine that divorce has been final for at least 15.) But having been to the group and talked to a few people there, I was now part of BYU’s secret underground cabal of gays. What’s more, since the guys I met were Snide Remarks fans, I was “in.”

• • •

One of them was a guy I’ll call Stan. He was soft-spoken and gentle, and very smart. Talking to him had a much-needed soothing effect on me. He was more experienced with the whole gay thing than I was — my only experience was being in musicals, and I’d only been in one, and I had a girlfriend during it — but I don’t think you’d say he’d “been around the block.” I think he’d just been down the street and back, maybe peered through a few windows.

Stan and I became pals, hung out now and then, and talked on the phone, which was the style at the time. We didn’t think of it as a “date” when, on April 22, 1998, we saw the national touring company of “Riverdance” in Salt Lake City. In addition to writing for The Daily Universe, I was also freelancing theater reviews for the Provo city paper, whose name escapes me now, and I took friends with me to shows all the time. Besides getting to hear Snide Remarks lines that the Communications Department made me cut out, it was the only real benefit of knowing me.

According to my review of “Riverdance,” the objectivity of which I cannot vouch for given what happens later in this paragraph, the show was fantastic. It was the end of the semester and Stan was leaving for some study-abroad thing in a few days, so our farewell when I dropped him off was fraught with emotion. Parked in Pedro outside the house that Stan shared with some of BYU’s other secret gays, I leaned over from the driver’s seat to give him a hug, which he reciprocated. The hug lingered, became more of an embrace, and then turned into a mutually tentative kiss, which soon became less tentative and more kissy.

This was not my first kiss, mind you. I had kissed one person before, that girlfriend I had my senior year in high school, when I was playing the Paul Lynde role in “Bye Bye Birdie.” Kissing Stan was basically the same as kissing her, only scratchier, and without her parents watching.

But aside from that girlfriend, Stan was the first person of either gender (we only had two back then) who’d ever indicated a physical attraction to me. I was a man of average handsomeness in college, not the 43-year-old cock-of-the-walk you see strutting before you today. People who liked me did so for reasons other than my looks. I had gotten comfortable with that reality and was by now only mildly jealous of hot people, but the notion of someone I was attracted to finding ME attractive and wanting to kiss me — in addition to thinking I was funny or whatever — was exciting and new, like “The Love Boat,” or at least like the theme song to “The Love Boat.”

Our kissing continued pleasantly for a while, me still in the driver’s seat, him still in the passenger seat, neither of us making any effort to escalate the situation. And then Stan paused the kissing, his face still close to mine, and softly murmured the words every man wants to hear:

“I can’t believe I’m making out with Eric D. Snider.”

Now, he said it with a smidge of irony. I had told him about my insecurity regarding friends vs. fans, and he was partly making a joke. PARTLY. He was also expressing sincere wonderment at sharing an intimate moment with a famous person, in a “wait’ll my friends hear about this…” kind of way. But Stan, being a gentleman, didn’t tell anyone, as far as I know. If he did, he’s retroactively dead to me.

He was out of the country for the rest of 1998. We kept in touch through email and resumed our friendship (platonic) when he returned, but a lot happened in between. As my campus notoriety continued to grow, I fell deeper into BYU’s underground (not literally) gay community, where I found acceptance and understanding I hadn’t felt before. Rob accepted and understood me, but we didn’t have much in common beyond our sexuality and our religion, whereas some of these other guys also shared my interest in theater, movies, and making fun of BYU — and, on top of that, some of them were attracted to me! And it happened so fast, and was so new to me, that it caught me off-guard. A lifetime of church instruction about Not Going Too Far with girls hadn’t prepared me for what to do when the girls were guys. The same principles applied, of course, but I hadn’t internalized them. I was like a soldier who’d trained extensively on what to do on a particular kind of battlefield, only to arrive in combat and find that the battlefield was different and the enemy was cute.

I met some good people and had some positive experiences, but I also met some lousy people and made some mistakes. I did things I knew weren’t right — which led to lying and sneaking around, which I also knew wasn’t right — and I violated BYU’s Honor Code. I was more concerned about the spiritual consequences than the academic ones, but the latter were more pressing in the short term, because the Honor Code Office is less forgiving than God is. If a faculty member or tattletale student had learned of my shenanigans, to say nothing of my tomfoolery, I could have been kicked out of school.

So all of THAT — being a campus celebrity while living a secret double life and having non-unrequited crushes and feeling anxious about everything while also, you know, going to school — hung over my head until I safely graduated in April 1999 with nary a run-in with the Honor Code Office (OK, there was one).

By this time my journal-keeping had become sporadic. My life had gotten so gay that there was no longer any way to write around it, but I still didn’t want to put it on the record. I somehow still thought, in the back of my mind, that I was going to (pardon the expression) straighten things out.

• • •

That farewell moment with Stan set me on what a hack writer would call “a journey of self-discovery” but which I would call “a decade of me being a three-alarm toilet fire.” I was often happy during this time, and I had some success and wasted a lot of money in a variety of entertaining ways, but on a personal level, I was a conflicted mess. I had strong convictions about how I believed God wanted me to live my life, and these were often at odds with how I wanted to live my life, or at least with how I wanted to live it at that moment. For a few years I went through cycles, back and forth between religious devotion and, uh, the opposite of that. I always believed in it, and I never wanted to not be a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but I felt like I had to be either gay or Mormon. I also had it in my head that if I wasn’t going to be a 100% Good Mormon, there was no reason to be even 1%. Sometime in 2002 I quit trying altogether.

For the next several years I was away from the church. (Having spent most of this column on events that spanned a few months, I’m now smashing several years into a single paragraph. This is quality writing.) Though still a member, I was, in Mormon terminology, “less active,” which is a polite way of saying “not at all active.” I never became an enemy to the church or stopped being a TBM. It’s not even that I thought I couldn’t live its teachings. I could; I just didn’t want to. And rather than keep the parts I did want, the parts I still found happiness in, I turned my back on the whole thing — “threw the baby out with the bathwater,” as they say. (How many times must that have happened for it to become a saying?)

But rejecting God and the church and community I’d known my whole life turned out not to be a solid plan, either. Eventually some difficult personal experiences served as a spiritual cinderblock to the head, and I had some epiphanies:

I did not choose to be attracted to men. (I already knew this one.)

If God had wanted me to stop being attracted to men in this lifetime, He’d have provided a way for me to do so.

Since He didn’t, that must mean that being attracted to men is what God wants for me.

Ergo, I don’t need to hide my orientation from God or anyone else, or compartmentalize it away from the rest of me. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

This new understanding pried open the drawer in the back of my mind where I’d shoved everything I knew about God, and flung the contents all over the place. I already believed that God loved me, that the gospel of Jesus Christ was for everyone, and that our lives are not our own to just do whatever the dickens we want. But whereas before I had thought those truths were at odds with my being gay (hence my shoving them in the drawer), now I realized anything that was true could be reconciled with anything else that was true. Instead of asking God to un-gay me and giving up when He didn’t, I should have been asking Him to help me understand and accept my gayness and how to make it work for me as a faithful Mormon. I needed to stop hiding things in drawers and get back on track.

It took a few more years, but now I’m at peace with being both gay and Mormon. I accept and am not ashamed of the one I didn’t choose, and I find happiness and satisfaction in living by the standards of the one I did. If I had my life to live over again … I’m not gonna lie, I would probably still kiss Stan. But I wouldn’t make the subsequent mistake of thinking faith was an all-or-nothing proposition. I would hopefully find the middle ground sooner, and realize that all I needed to straighten out were my priorities. The real Snide Remarks … was love. Which doesn’t even make sense.